Written by Ry Emmert and originally published in Belmont Citizens Forum’s September Edition.

Understanding Clay Pit Pond and Belmont’s Hidden Rivers

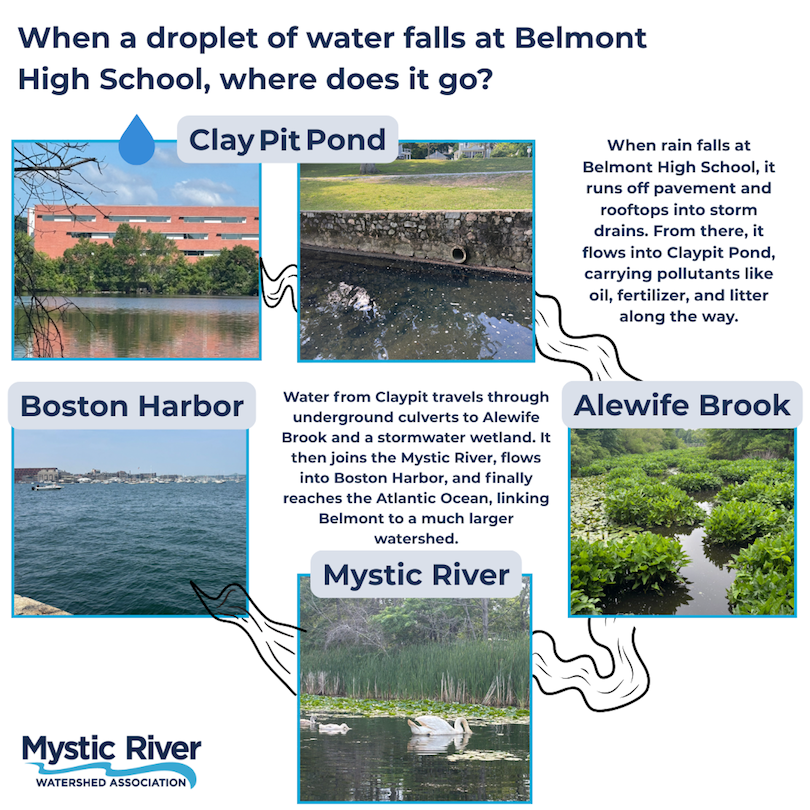

People don’t often think about where a raindrop goes after it hits the ground. It may splash on the pavement, flow toward a storm drain, and then seemingly disappear. However, if that droplet falls outside Belmont High School, it embarks on a complex and unexpected journey. This journey connects Belmont’s sidewalks to kayakers on the Mystic River, fish in the Charles River, and ships in Boston Harbor.

The story begins with Clay Pit Pond, a shallow and iconic body of water situated between the high school and Concord Avenue. For many residents, it serves as a scenic backdrop, a place to walk, jog, or sit and take in the surroundings. To others, it appears as a polluted pit, clearly marked with health warnings. What most people don’t realize is that Clay Pit Pond is not a closed system. Instead, it acts as a gateway, a crucial pass-through point in a vast and often hidden network of stormwater infrastructure.

Flow chart of water’s pathway from Clay Pit Pond through Alewife Brook and the Mystic River to the Boston Harbor.

Belmont’s hidden waterways

Clay Pit Pond is part of the Mystic River watershed, a 76-square-mile area that drains parts of 21 cities and towns into the Mystic River and, eventually, the Boston Harbor. When rain falls in Belmont, it doesn’t soak quietly into the soil. It moves over sidewalks and rooftops, through storm drains and pipes, into ponds and streams. The infrastructure guiding this water is largely hidden in old underground culverts and stormwater mains that weave beneath neighborhoods and town lines.

Near Belmont High School, stormwater outfalls on the west side of Clay Pit Pond collect runoff from roads, parking lots, and rooftops. The water picks up everything it touches: oil drips, pet waste, fertilizer, road salt, and sediment. It briefly enters Clay Pit Pond, then exits via a culvert beneath Concord Avenue, flowing into Wellington Brook. From there, it travels underground again to Blair Pond, Little River, Alewife Brook, Mystic River, Boston Harbor, and, eventually, the Atlantic Ocean.

All of this movement happens mostly out of sight. Few people realize that Belmont stormwater connects directly into Cambridge’s system, or that Belmont’s runoff travels through Wellington Brook into Alewife Brook. The result? A system where responsibility is shared, and consequences are, too.

A pond under pressure

Despite progress across the Mystic River watershed, Clay Pit remains persistently polluted. Why? The answer lies in both what’s visible and what’s hidden.

One major issue is aging infrastructure. In some cases, sewage is leaking into stormwater pipes through cracks or illicit connections, or old pipes that are mistakenly tied into the wrong system. These cross-connections are hard to find and expensive to fix. Yet they’re a major reason why nearby Winns Brook, which shares this system, received a “D” for bacteria on a recent Mystic River Watershed Association (MyRWA) report card. Clay Pit Pond likely faces similar contamination from diffuse wastewater sources.

Another problem is sedimentation and nutrient loading. Water running off Belmont’s streets carries phosphorus from leaf litter, pet waste, and fertilizer. That water settles into Clay Pit Pond where it delivers nutrients that can lead to algae blooms and other ecological imbalances.

Sediment from erosion—including from disintegrating banks and disturbed soils—builds up, making the pond shallower. You can see the effects yourself: short-legged ducks and geese now wade far from shore, closer to the high school’s grounds.

Finally, the pond carries a historical burden. Sediment cores have revealed pesticide residues from the 19th and 20th centuries. Long-banned chemicals are still lingering at the bottom.

A path forward through collaboration

So, what actions can Belmont residents take to make a difference?

Longtime local advocates like Anne-Marie Lambert have consistently emphasized that real change starts with public awareness, and with caring enough to act. In her many articles for the Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter, Lambert has traced how aging stormwater infrastructure, invisible culverts, and fragmented public understanding have hindered efforts to build momentum around water quality. Much of the problem, she’s noted, lies in what people can’t see: polluted outfalls tucked behind buildings, buried pipes that cross town lines, and sediment slowly accumulating out of sight.

Lambert is now helping to launch a new community group, Friends of Clay Pit Pond, in hopes of turning a familiar neighborhood landmark into a center of environmental engagement. The group aims to highlight how Belmont’s stormwater challenges are tied to a wider regional system, and to show that local action, even on seemingly small scales, matters.

Other promising steps are underway. The town has invested nearly $2 million over the past decade to identify and repair leaking pipes. Green infrastructure features like rain gardens and infiltration trenches are being explored as more affordable ways to slow and filter runoff. And the Department of Public Works (DPW) is proposing expanded public education including outreach to landscapers, homeowners, and neighborhood groups about small-scale actions that can reduce pollution at the source. [The Belmont DPW Engineering Department recently hired a stormwater supervisor to ensure compliance with ever-changing requirements and MassDEP mandates, inspections and reporting. – Editor]

Still, the scale of the problem is significant. Much of Belmont’s runoff flows through just a few key outfalls, and only a small percentage have undergone full dry-weather inspections. With many pipes still uninspected and more breakages likely to emerge, sustained investment and public engagement will be essential.

But one thing is clear: restoring the health of Clay Pit Pond and the Mystic River watershed is not just the job of town staff or engineers. It’s a shared responsibility; one that begins with paying closer attention to the water beneath our feet and taking action in our own communities.

What you can do

Volunteer with the Mystic River Watershed Association:

Sign up to become a water quality monitor or participate in local cleanups.

Visit the calendar on the MyWRA website, www.mysticriver.org, and subscribe to MyRWA’s newsletter for upcoming volunteer events.

Get involved here: mysticriver.org/volunteer

Learn more

Explore how stormwater impacts local ecosystems and what’s being done: mysticriver.org/stormwater

Track combined sewer overflows (CSOs) and their impact: mysticriver.org/csos

Advocate locally

Attend public meetings in Belmont and neighboring towns.

Voice your support for green infrastructure projects and long-term investment in stormwater solutions.

Encourage collaboration across town lines (especially with Cambridge and Arlington) to build a more resilient watershed.

Join Belmont’s new Friends of Clay Pit Pond group. Email bcfprogramdirector@gmail.com for more information.

In the end, a raindrop that falls outside Belmont High School doesn’t just vanish. It flows through culverts, into ponds, along brooks, and down rivers. It picks up pollution from four municipalities. It passes kayakers, flows under the Earhart Dam, and enters the sea. Our responsibility to that water doesn’t end at our storm drain, and neither should our care for it.

Ry Emmert is a senior at Williams College majoring in Geosciences and Coastal and Ocean Studies. Ry joined MyRWA as an Environmental Science and Stewardship Fellow for summer 2025 through the Yale Conservation Scholars Early Leadership Initiative program.