BOSTON — For the first time, the Mystic River, Charles River, and Neponset River Watershed Associations have collaborated on their grading calculations and river report card announcements, which were made today, July 14, 2021 at Deer Island.

EPA New England and many partners have worked hard for decades to improve the water quality in Boston Harbor. In addition to the sewage treatment infrastructure built by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority at Deer Island, and elsewhere around the harbor, significant effort has focused on water quality in rivers discharging into the harbor. This work has been done in partnership with the three local watershed organizations that are committed to field efforts to gather water quality data to quantify levels of bacteria and other contaminants in both dry- and wet-weather conditions. This citizen science contribution of water quality data assists local, state and federal officials to target resources strategically, directing effort to areas most at-need, and ultimately ensuring the three urban rivers have clean, and safe, water to support recreation and enjoyment for all Boston-area residents and visitors.

"The contributions of citizen scientists to our efforts to improve water quality in these urban rivers cannot be overstated," said EPA New England Acting Regional Administrator Deborah Szaro. "EPA is grateful to the three watershed associations for the scientific data collection that has helped us to direct our resources to the most critical areas in need of attention. By highlighting locations with water quality impairment, we find that we are also directing our action to improving environmental conditions for historically underserved environmental justice neighborhoods."

Overview

During the past 30 years, the focus of improving water quality in Boston Harbor has transitioned from addressing major outflows of raw sewage being discharged into the Harbor to identifying and addressing numerous smaller sources of bacterial and other contamination further up the watersheds that discharge into Boston Harbor.

The three watersheds make up a significant portion of the freshwater inputs to Boston Harbor, and all three have an impact on Boston Harbor water quality. Just as each watershed is unique, there are slight differences in how each watershed association calculates the grade. However, the grades provide a science-based indication of what many Boston-area residents may not have realized – that bacteria concentrations in the harbor and the rivers are low in dry weather, but that there are significant problems during and after rainstorms, as well as localized problems in some of the tributaries to the rivers. Efforts are continuing to tackle these remaining problems so that all residents of Greater Boston can enjoy the benefits of clean water.

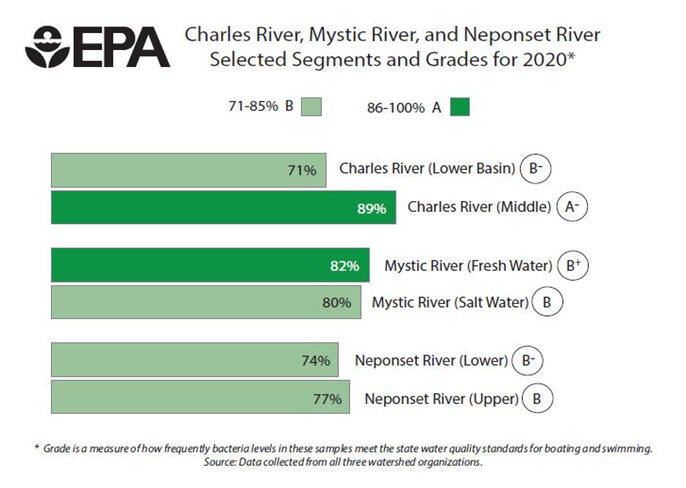

The grading systems are based on the percentage of time bacterial levels in the water meets swimming and boating standards for recreational safety during wet and dry weather. Boating standards are often met throughout the watersheds, while swimming standards are typically met in dry weather but continue to be impacted by precipitation events. All three grading systems use a three-year rolling average, which helps account for interannual variation in the weather.

All three report cards would not be possible without the hard work and dedication of dozens of citizen volunteers who collect monthly water quality samples in the early morning throughout each watershed. Without this army of dedicated volunteers, EPA or the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) would not be able to acquire detailed water quality data over time.

"The Baker-Polito Administration remains committed to working with communities to address water quality issues," said Eric Worrall, MassDEP's Northeast Regional Director. "The investment of over $225 million to improve wastewater, stormwater and combined sewer systems infrastructure in the Charles River, Neponset River, and Mystic River watersheds, has led to significant improvement in the water quality in all three of these important Commonwealth resources. We continue to be proud of our partnership with watershed associations and the EPA. The information we receive from citizen scientists helps to inform policy decisions that lead to cleaner waterways in the Commonwealth."

Mystic River Watershed

Continuing patterns from recent years in the Mystic Watershed, the main stem of the Mystic River received grades in the "A" to "B" range, with several smaller tributaries receiving poor grades, such as an "F" for Mill Creek in Chelsea and a "D" for Winns Brook in Belmont.

"The good news is that the Mystic—like each of the three great rivers of Boston Harbor—is a relatively clean urban river, safe and accessible for a variety of recreation. This news represents a great success story of the Clean Water Act, and its 50-year history of improving environmental and even economic conditions in cities. But there is still work to be done, and the report card we publish with EPA's collaboration shows where effort should be directed on the ground," said Patrick Herron, Executive Director of the Mystic River Watershed Association.

Neponset River Watershed

This year marks the first time the Neponset River Watershed Association has announced individual report card grades based on the data for streams throughout the watershed. The organization has been collecting watershed data since 1995, and currently samples 41 sites throughout the watershed monthly, from May through October. Sites are sampled on the mainstream of the Neponset River, smaller tributaries, and ponds.

In the Neponset Watershed, most segments rated in the "A" or "B" range, with Unquity Brook, Purgatory Brook, Germany Brook, and Meadow Brook rating in the "D" to "F" range. The grades for the main portions of each watershed, where most recreation occurs, were mostly in the "A" or "B" range. In addition to grades for bacteria, the Neponset River Watershed Association prepared separate grades for phosphorus and dissolved oxygen, which are important for fish and wildlife as well as recreation.

"The cleanup of the Neponset and its tributaries has come a long way, and it's gratifying to see so many more people out discovering and enjoying the river as it has gotten cleaner," said Ian Cooke, Executive Director of the Neponset River Watershed Association. "By continuing to find and fix sewer defects, and by working with private and municipal partners to solve the big challenge of polluted rain runoff from roads and parking lots, we will make the river an even more valuable resource for recreation and fish and wildlife in all our communities, including our environmental justice neighborhoods," Cooke added.

Charles River Watershed

Similar to trends identified for several years, five out of six segments in the Charles Watershed were graded in the "A" or "B" range, with Muddy River being the lone exception with a "D-".

In addition to grades for E. Coli bacteria, the Charles River is separately graded on cyanobacteria blooms and Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) discharges, which are both public health hazards, especially for boaters and other people coming into contact with the water when these contaminants are present. Cyanobacterial blooms, which have occurred with greater frequency over the past several years, are caused in part by excess phosphorous washing into the watershed from lawns and impervious surfaces. CSO discharges occur when heavy precipitation events overwhelm portions of the sewer system, and discharges of sewage mixed with stormwater are necessary to prevent sewage backups into streets and residences.

"The wide variety in Charles River grades from an A in the middle watershed to the D- in the Muddy River reflect the predominant land use around each area. Areas with more development and impervious surface are more polluted. We have work to do to restore all areas of the Charles to be ecologically healthy," said Emily Norton, Executive Director of the Charles River Water Association.

Sewage Connections and Nutrient Runoff Concerns

Many Boston Harbor watershed communities continue to struggle with identifying and removing sources of sewage that discharge to the rivers directly or through vast networks of storm drains. In addition, while CSOs have been significantly reduced over the years, they still occur and can impact water quality.

Since 1985, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) has worked with EPA and MassDEP to design, construct, and operate one of the largest wastewater collection and treatment systems in the country. MWRA has closed 35 CSO outfalls and reduced CSO discharges by approximately 87%. MWRA, in coordination with EPA and MassDEP, is currently analyzing whether the work conducted to date is sufficient, or whether additional projects are warranted.

"While there is still work to do, our progress to date has transformed Boston Harbor and its tributary rivers," said MWRA Executive Director Fred Laskey. "MWRA is happy to be able to provide laboratory services to the watershed organizations. It helps the public stay safe while enjoying these recreational resources and it helps us focus on areas that may need more work.

In addition to E.coli bacteria, sampling results indicate other problems faced by all three watersheds. Precipitation events continue to wash phosphorous and other pollutants off lawns or impervious surfaces (streets, parking lots, rooftops, etc.) into local waterbodies, causing excess plant growth and, in some cases, cyanobacteria blooms.

EPA has also taken additional actions to address elevated levels of nutrients that are harming water quality throughout the Charles River Watershed, with an eye toward how a similar approach would work in the Mystic and Neponset Watersheds. Last year, EPA conducted a wide-reaching process to gather stakeholder input about a potential path to address stormwater runoff from commercial, industrial, institutional, and residential properties in the Charles River Watershed that are not currently regulated. EPA is currently evaluating that input along with existing data and expects to make a decision by the end of the year.