Bacteria Pollution in the Mystic

One of the leading pollutants in our water is bacteria, single-celled organisms that are neither plants nor animals. Of course, bacteria are everywhere, and most of them are harmless. The bacteria that we are concerned about in our rivers, lakes, and streams are pathogens–organisms that cause disease. So, where do these pollutants come from?

The pathogens water quality managers focus on come from feces. How does fecal waste get in rivers and streams in quantities that could affect public health? The main source is raw sewage from our sewer lines making its way into our waterways through Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) or leaky pipes—another source is pet waste.

How do we know that raw sewage getting into our water?

For several years, MyRWA, in collaboration with US EPA, organized a “hotspot” monitoring program that tested the water coming out of stormwater outfalls (the ends of pipe networks) primarily during rain storms. The map shows results from our hotspot testing at outfalls over the years. The map shows the percentage of samples that exceeded EPA recreational standards for swimming and boating. As you can see, pipes with problems are distributed across the watershed, in all municipalities. Click on the points for more information including how many samples are represented in this data.

The impact of bacteria on stream water quality can be seen in the water quality report card we issue every year with EPA.

How does the pollution get in the pipes?

There are a few mechanisms that allow wastewater contamination into stormwater systems:

combined sewer overflows

illicit connections

leaky and broken pipes

sanitary sewer overflows

pet waste

Combined Sewer Overflows

Adapted from EPA.gov

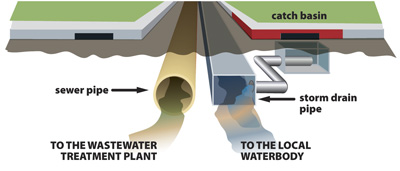

Most of the time, wastewater sewer and stormwater pipes are separate systems. Wastewater is directed to a wastewater treatment plant. In greater Boston that means mainly the huge wastewater treatment plant run by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) on Deer Island in Winthrop. Stormwater from roads and rooftops, on the other hand, is directed through storm drains and pipes to the nearest waterbody. But in some older areas of urban systems there are combined sewers, where stormwater from streets and wastewater from homes and other buildings are sent in the same pipe to the wastewater treatment plant.

What happens in combined sewer systems?

In a combined sewer systems, most of the time sewage goes to a sewage treatment plant (Deer Island), along with any stormwater from light rain that the pipe has capacity to carry to the treatment plant.

However, during periods of heavy rainfall or snowmelt, the amount of rain water in a combined sewer system can overwhelm the system. In these cases, the combined sewer systems are designed to overflow— instead of backing up into houses and streets—and to discharge directly to nearby streams, rivers or other water bodies. These pipes emptying into rivers and streams are “combined sewer overflows,” or CSOs.

See this video for a helpful animation showing how CSOs respond in dry weather, light rain and heavy rain.

CSOs are a major target of environmental regulation. Eliminating CSOs has been a major tool in the historic cleanup of Boston Harbor over the past thirty years. Eliminating CSOs on the Mystic, Charles and Neponset Rivers, as well as CSOs that emptied directly into Boston Harbor has helped turn the “dirtiest harbor in America” into what’s been called “a great American jewel.”

But CSOs remain, and continue to be significant sources of pollution.

Are there CSOs on the Mystic River?

Currently, there are CSOs along the Alewife Brook, Mystic River and Chelsea River. Annual discharges from CSOs— although much reduced— are still measured in the millions of gallons. The map shows currently active CSOs and ones that have been eliminated. This table to the right shows specific progress in the Mystic. It shows the volume (in millions of gallons) of CSO discharges in 1992 and 2017, and compares those numbers with the goals announced in the Long Term CSO Control Plan (LTCP), mandated by federal court order. Much progress has been made since 1992, but these pipes remain significant sources of contamination. Some CSOs have local treatment facilities that treat the water with disinfectant. The final column shows the percentage of total volume that gets this minimal level of treatment before discharge.

The Massachusetts Water Resource Authority is working to eliminate CSOs, and to keep the public informed when CSOs happen. You can sign up for notifications or read about overflows in Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea and Somerville.

Illicit connections

Image courtesy of Department of Public Works, Anne Arundel County, Maryland

An illicit connection is when a sanitary sewer pipe from a house or business is illegally or unknowingly connected to a storm drain instead of the correct sanitary sewer main. For example, if a sink, toilet, or laundry machine is connected not to the sewer system but the stormwater system, then sewage and other contaminants make their way directly into our rivers, lakes, streams and ponds. These illicit connections get buried and then forgotten. They can remain undiscovered for decades.

Old Infrastructure

Cracks in old stormwater and sewer lines can lead to cross contamination—allowing sewage to make its way from cracked sewer pipes (headed to Deer Island to get treated) to cracked stormwater pipes (headed to the closest water body). This probably the most widespread chronic cause of wastewater pollution in our waterways. It’s also probably the hardest source to track down and among the costliest to fix.

Sanitary Sewer Overflows

Like CSOs, Sanitary Sewer Overflows (SSOs) usually happen during heavy rain events when stormwater infiltrates and overloads the sewage system, but can also happen due to improper maintenance or vandalism. The EPA estimates that there are at least 40,000 SSOs each year across the US. Recurring SSO sites exist throughout the Mystic River Watershed.

Pet Waste

In 1991 the EPA designated pet waste as a source of pollution, on par with herbicides, pesticides, oil, grease and toxic chemicals. In addition to e.coli and fecal coliform, which causes cramps, diarrhea, intestinal illness, and even kidney disorders, dog waste can contain giardia, salmonella and roundworms.

The EPA estimates that two or three days’ worth of droppings from a population of about 100 dogs would contribute enough bacteria to temporarily close a bay, and all watershed areas within 20 miles of it, to swimming and shell fishing.

Luckily, the solution is simple. Pick up after your pet and encourage others to do so!